Check out the short video Quiet Mind, Endless Sea: Part 1. It describes how I found the Crealock 37 and began preparing her for a voyage across the South Pacific voyage. See my puppy Little Bear’s reaction to going aboard Pamela.

The Spinnaker

It was a positive feeling of sweet ecstasy. I drifted down off the cloud and felt my body settling down back on Earth. I tried singing the chorus to Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah but not much sound came from my lips. Pam was massaging my feet and Dr. Shinghal was asking me how I felt.

“Really great. Can we do this again next week?”

He smiled. He knew the anesthesia would soon wear off and I would realize I had a catheter sticking out of my John Thomas and I wouldn’t feel like singing Leonard Cohen.

What had I just been dreaming of? Ah yes — sailing Pamela fast downwind on a broad reach through warm tropical waters.

A man moaned silently behind a curtain next to me. “How is the pain now?” a nurse asked him.

“Oohhh…” he murmured. I felt a rush of compassion for him. A hospital is a good place to come to feel compassion.

I had been worried about this prostate procedure. The previous weeks had been full of apprehension and imagined side affects.

What if they cut off my member by mistake and then sewed it to my forehead, so that every time I got excited I looked like a unicorn?

The man moaned again. The nurse asked Pam to leave the shared recovery room so the man could have some privacy.

I closed my eyes and listened to the heart rate monitor beside me. Could I change my heart rate just by thinking about it? With a few deep breaths I found I could. The beeping slowed a bit, then rose as I thought of things I had to do, like preparing Pamelafor extended offshore cruising. A couple deep breaths, imagining myself under a mango tree in Kalalau Valley in the remote northwest corner of Kauai. Sure enough, the heart monitor slowed its pace. Experimenting further, I imagined I was in a staff meeting at Apple discussing deadlines, constrained resources, and online payment methods in emerging markets. There was a perceptible uptick on the monitor.

How long would I be in this recovery room? I wanted to get back to my reading of Offshore Cruising Companion. I noticed my stomach tightening, and with an out-breath I let the tinge of anxiety go. I closed my eyes again and practiced not thinking. I’m getting good at not thinking (not!) — I can now go for nearly 15 seconds before my mind resumes its assembly line of mundane headlines. As my mind began to drift I thought of flying Pamela’s spinnaker on a downwind run.

What a spinnaker! With red, white, and green markings it resembled an Italian flag and made me hungry for a pizza. It seemed brand new when I first pulled a corner of it from its sail bag last year. For over a year it lay in the sail bag as I constantly hauled it around the boat’s cabin looking for a better place to stow it. But I was afraid of it. I was frightened of wrestling down a full spinnaker in a rising wind while driving Pamela’s 16,000 pounds over breaking waves at eight knots. Out of the sail bag I pulled only a small section of sail. I saw that it had a “sock” device and some heavy bits of hardware attaching it to the sock.

“What kind of spinnaker is it?” asked TJ, my sailing instructor. “Is it symmetrical, asymmetrical, or code zero?”

“Oh .. it’s asymmetrical I think, or maybe its symmetrical.”

He looked at me with his head cocked to one side. “Does it have sheets or guys? How does it tack down? Do you have a pole?”

“Well, um, yes, I think there’s a sheet. There’s some lines sticking out…”

“Have you hoisted it?”

Hoisted it? I was afraid to take it out of the sail bag. How could I possibly hoist it? I didn’t even know what sort of spinnaker it actually was. I managed to convince TJ that I had absolutely no clue about my spinnaker, nor whether it even was a spinnaker.

“We should take a look at it,” he suggested. “You’ll want it when you sail the downwind trades to Polynesia.” TJ was teaching a spinnaker class on a 35-foot “J” racing boat. On the lightweight J/105 I handled the asymmetrical spinnaker with ease and even managed to gybe it singlehanded in full control by the end of the class. Pamela’s rig is larger and heavier than the J and seemed to me like it was orders of magnitude more complex. Having TJ show me how it worked would be a smart move. Did I want to actually fly Pamela’s spinnaker to the Marquesas or just pretend, telling other sailors, “Oh yes, I have a spinnaker. It’s in that bag right there. I haven’t figured out how to get it out of the bag. Here, let me move it off this seat so we can sit and have a beer.”

So I did some homework before TJ came to the boat. I pulled the spinnaker from the bag — so far so good — and then hauled it up through the forward hatch and onto the deck. Johnny M was there to make sure I didn’t pitchpole or capsize while Pamela was tied fast to the dock. We found the sail’s head, tack, and clew, fastened the spinnaker halyard, and then raised it a few feet off the deck.

“You see how this sock works?” Johnny M pointed to the bell-shaped fiberglass ring on the end of what resembled a giant sausage casing. “This line raises the sock, which uncovers the sail, and this one covers it back up as it lowers the sock down over the sail. Simple.”

“What if something happens?”

“Like what?”

“Well, what if it gets out of control or there’s a flying uncontrolled gybe, or maybe a broach?”

“Then you lower the sock and take the sail down.”

“And what if you can’t lower it because there’s too much force on the sail and a line squall is coming up fast on the horizon?”

“You can lower it. You sail a little further downwind to blanket the spinnaker with the main and this takes the pressure off the spinnaker, and then you can pull the sock down over it. It’s easy. It’s not rocket science.”

To Johnny M, nothing on a boat was rocket science. It was just “stuff” and you could figure it out. Except my SSB and SailMail modem with counterpoise antenna interfaced with GPS and AIS. To Johnny M, that was closer to rocket science. But a sail was a sail, and a spinnaker was just a big sail, and this particular spinnaker made you hungry for a pizza. It might be hard to get a take-out pizza in the Tuamotu Archipelago, but sailing there with this spinnaker would be easy.

And thus I learned that Pamela’s spinnaker was asymmetric — a modern, easy-to-handle design — nearly brand new, and could probably be handled by Pam and me without much yelling and cursing.

A few weeks later I met TJ on the boat and we rigged up a collar to hold down the tack of the sail and sheets on port and starboard to control the trim. No foreguys, after-guys, or spinnaker pole necessary. We were expecting light winds as we exited South Beach Harbor but the breeze soon began to build to 15 knots from the southeast, an unusual direction for Springtime on San Francisco Bay. As we raised the main and jib to sail further into the bay we tucked in a reef and then discussed once again the procedure for hoisting the spinnaker and controlling it.

The moment of truth had come.

“OK, here we go!” said TJ.

“Let’s do it!”

I pulled the halyard to raise the spinnaker in its sock to the top of the mast, in control while TJ held the sock’s control lines and the autopilot steered Pamela in a deep broad reach 160° off the wind.

“Do you want to steer and trim while I release the sock?” TJ suggested.

“Sure,” I agreed and moved back to the cockpit to switch off the autopilot, taking the helm in my right hand and the spinnaker’s lee sheet in my left. My heart was beating in my ears. It made good sense to have TJ on the foredeck in case anything weird happened while the sock was going up and letting the beast out of its cage. I was aware of how a spinnaker can suddenly fill with air and make a sharp crack as it snaps into place, and how it can just as easily lose all its wind and take a few turns around the forestay. I’d experienced both of these on the lightweight J/105. I’d also read the reports of the performance boats sailing to Hawaii in the Singlehanded Transpac. The most frequent repairs and mishaps on these boats were spinnakers ripped in half by a freshening breeze, broken shackles holding the spinnaker in place, or a spinnaker hopelessly wrapped around the forestay with some of its parts filling with air on an approaching squall that ripped the sail into tattered bits cracking away in the shrieking wind.

“Ready?” shouted TJ from the foredeck.

“Let ‘er rip!” I whooped. Not the best choice of words when you’re flying a sail.

Pamela is like Sophia Loren. She is beautifully curved and strikingly feminine. You don’t ask her how old she is. The world turns its head to watch as she walks gracefully past, and she does nothing in haste. She released her spinnaker with Italianate grace and style and presented it to the winds now reaching 18 knots. The big sail filled beautifully. Pamela responded and came up to speed.

Click the image above to see the video

“Yahoo!” I shouted as my mouth watered for pepperoni.

“She’s a beauty,” agreed TJ. “Look at how she sails — such a controlled, easy motion. How is she at the helm? Come up a bit.”

I stopped dancing just long enough to come up 5° and trimmed in the sheet. “Very easy on the helm. The sheet also feels good, not too much torque on it.”

The luff of the spinnaker curled slightly to weather. I recalled how the J/105 had done that when it was well-trimmed. “That looks great,” said TJ. “Curling just a bit to weather like that. Really nice.” We were moving now at about six and a half knots and the feeling was one of sheer pleasure, as when a man and his machine are aligned with the natural forces at peak performance. Pamela raced through the water with a sea-kindly motion without rolling or rounding up into the wind.

It was a positive feeling of sweet ecstasy and made me want to burst into Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah. How great this will feel on the ride down to Mexico come October, and across the trades to French Polynesia next March.

Dr. Shinghal roused me from my reverie and asked once again how I felt. The anesthesia was gone now and the pain killers were fading, yet the catheter was not particularly uncomfortable. Dreaming of Pamela I hadn’t even noticed it.

“We’ll serve some lunch soon and then dinner,” announced the nurse. “What would you like? We have salmon, chicken, or quiche. The mashed potatoes are home-made.”

“Did you make them?”

“Well, no. They are made here at the medical center.”

“Is this home?”

She looked at me with suspicion.

“How about a pepperoni pizza?” I quipped.

“Uh, no.”

Setbacks and Revelations

The night air had a bit of a nip in it, but not so cold now that Spring was in full swing. The thought of crawling into my bunk in the forepeak was comforting as I made my way down the long dock to Pamela waiting for me at the end. My dream ship, waiting for me there in the night, silently tugging on her mooring lines. I came easily aboard in the dark and felt my way to her companionway, slid open the hatch and peered inside. Total blackness, no marine smell, and curiously no sound from the de-humidifier. I stepped in and climbed down the ladder.

Slosh! My shoe filled with ice-cold water. My boat was full of water!

Instantly I switched on a light and found six inches of water and floating floor boards. The hatch covering the fuel tank was lifted by a stream of water. It was a very terrible, agonizing sight.

I quickly tasted the water — salty. But my bilge pump — why was it not sucking this water out of my boat? I went to the pump switch and switched it back and forth — no response, no sound from the pump.

The message rang out loudly and clearly in my head — my boat was sinking!

Like hearing the bark of a wolf under a full moon while you crawl deeper into your sleeping bag beside a dying camp fire, my mind and body filled with raw, primitive fear.

What do you do when your boat is sinking? My mind raced. Whatever it is, you had better do it fast.

Taking off my shoes and socks and rolling up my pants I began a systematic search of all the ship’s through-hull valves, also known as seacocks. Every boat has them — actual holes in the boat to let water in and out. The engine needs seawater for cooling and then has to push it back out of the boat. The head needs seawater for flushing and the sinks need to drain. The air conditioner cycles seawater in and out to cool or heat the boat. Pamela has 15 seacocks in all. It was likely that one of the seacocks below the water line had breached, or a hose connected to one of them was leaking.

I closed the valves in the head, the galley, the air conditioner, and the engine intake, then ran up the ladder to the cockpit to find the manual bilge pump. I was thankful that I had tested it previously and knew exactly where to find the pump handle and how to fit it properly into the pump. But I had no idea how fast it would work and whether it could get all that water out. I pumped away for several minutes with deliberate and rhythmic strokes, conscious that I might be pumping for a long time.

I did not want to look into the cabin to see how much water was remaining. Just keep pumping. Switch arms before you get too tired, and imagine you may be doing this for a few hours.

After several minutes I dared to look down into the cabin. Good news — a few inches of water were gone. The floor boards were no longer floating. I called Pam. We were planning to rendezvous on the boat for the night, then attend a cruising seminar the following day.

“Pam! I need your help. The boat is full of water!”

“That’s not good,” she said. I know it’s not good. With my shoes full of water, my face covered in sweat, and my boat sinking in her slip I can tell you exactly how not good it is.

Pam arrived a little while later and helped me finish the pumping, and together we dried what we could with towels. We seemed to have the situation under control. A small amount of water remained at the bottom of the bilge, but the level was not rising. I arose a few times in the night to inspect the water level and tried hard not to think about what could have happened if I hadn’t planned to be on the boat that weekend.

We left the boat the next morning with her port holes and hatches open. I left a note on my buddy Johnny M’s boat to explain why Pamela was opened up and drying out. Johnny M would likely be on the dock that day, and he would be puzzled to find the hatches open and me gone. I knew he would keep a weather eye out for rising water in Pamela’s cabin. He was as stout and solid as a post, and he taught me a great deal about how to take care of my boat.

The cruising seminar was taught by two famous round-the-word sailors, John and Amanda Neal. I introduced myself to both of them straightaway and announced that last night I came aboard my Pacific Seacraft 37 to find her with a faulty seacock and a failed bilge pump, sinking in her slip. They have tons of sailing experience, and for some reason I felt the urge to tell them this.

“That’s not good,” decided John Neal.

The day was filled with a thousand facts, observations, and warnings about ocean cruising and passage-making. It was good stuff, some that I knew, much that I learned. But combined with the uncertainly of what was going on with Pamela’s plumbing, it brought on more trepidation and worry for Pam and me. The fellow cruisers we met during lunch were supportive and helpful. They all agreed that a boat full of water was not good. One man was preparing for a circumnavigation, and thought maybe my problem was the “dripless” seal between the propeller shaft and the transmission. The propeller shaft is yet another hole in the bottom of a boat, and there is a very important seal that prevents seawater from entering. On Pamela, there is a state-of-the-art seal called a “dripless” shaft seal, which works on the principle of two metal plates pushed tightly together to allow the propeller shaft to spin yet prevent water from entering. It is typically very reliable, but when it breaks it can go from dripless to spraying salt water all over your engine and flooding your boat.

A report came later that day from Johnny M. There was a few inches of water in the bilge and maybe it was rising.

“Let’s not stay for dinner,” I suggested to Pam. “Although I’d like to get to know these other cruisers, I need to get back to the boat and check on that water level.”

This problem with the boat’s plumbing was happening at a time when my own plumbing was called into question. A month earlier I had a blood test done as part of a routine physical exam. The lab results came back with a “high PSA alert” — meaning, something was wrong with my prostate. A visit with a specialist revealed an internal infection likely caused by an enlarged prostate, possibly cancer. The recommendation was a series of tests and a special surgery to cut away at the prostate. Tubes, probes, and catheters going into all the places you cannot discuss in mixed company. Enough to make even John Wayne want to sit with his legs crossed.

In a couple more weeks I would be unemployed. My plan was to leave Apple in the middle of April to begin preparing Pamela, Pam, and me for the two-year odyssey to New Zealand. I had announced this five months earlier to my management team and had systematically prepared my staff to take on all the initiatives that I was running. But how could I quit work and I take on unexpected and significant hospital bills if this prostate thing turned out to be cancer? Yet the voice in my head was clear: this was my path and I had chosen it.

Tax season brought even more financial worries. It was about this same time that I prepared our 2012 income taxes — whump! Although the Apple stock had fallen 40% in value over the past six months, by cashing out I now owed the tax man more money than I had paid for Pamela! The cash I had saved and set aside for “retirement” was dwindling fast.

A sinking sailboat, possible cancer, unemployment, and signifiant loss of wealth — April was turning out to be a bad month.

Back at the dock I half expected to find Pamela completely submerged with only the top of her mast exposed. What I relief when I found her afloat in her slip with a dry salon and the water level in the bilge continuing to hold steady. I inspected the dripless shaft seal and found that with a little bit of pressure I could easily move the metal plates and cause a small squirt of water to enter the boat. Was that supposed to be normal? My mind churned through the possibilities — should I get a tow boat to pull her across the bay to the yard that had recently replaced her rigging and installed the new feathering propeller? Should I continue to monitor the situation until I could spend more time troubleshooting next weekend? Should I drive back up to San Francisco tomorrow night to check on her? What should I do right now?

That night I did some research on the dripless shaft seal to understand how it functioned. It seemed reasonable that my forced movement on the device could cause some water to enter, and I had definitely jerked hard on it to see what would happen. I also noted that all new Pacific Seacraft 37 sailboats, well known for their ocean-going qualities, come with the dripless shaft seal installed. The next day I called the manufacturer and spoke with a knowledgable technician who explained that it was indeed possible to pull back on the shaft bellows with your hands and cause the carbon rotor to slip slightly from the stainless steel plate, causing some water to enter. Then letting go of the device, the bellows would push the rotor hard against the steel plate again and prevent any more water from entering. It seemed very reasonable from a mechanical perspective, and my mind eased a bit. If the shaft seal was not the source of the leak, then no more water would enter the boat as long as I had the seacocks closed.

A few nights later I was lying in a hot bath tub that Pam had prepared for me — full of borax, baking soda, and hydrogen peroxide to release a lifetime of toxins that she believed were responsible for my enlarged prostate.

“Cut the deck”, said Pam. She had a stack of Tarot cards and decided it was time to give me a reading. I was curious about Tarot, but my analytic mind believed that the process of choosing a card from a deck of 78 was too arbitrary for me to believe in. “Now choose one”, she insisted. I went along with it. I didn’t feel any supernatural urge to choose a particular card. I mindlessly selected one from the middle of the deck.

“Oh! The moon! That’s a great card for you.”

“What does it mean?” I was curious.

Pam began to read from the book Tarot of the Spirit by Pamela Eakins. I had met the author a few weeks prior at a seminar at a funky east-meets-west bookstore. I was impressed with her knowledge, but she came across a little scattered-brained and rambling. Her hair was long and white, quite attractive, and not too different from Saruman the White in Lord of the Rings, the power-hungry wizard who attempts to help the Dark Lord Sauron take over Middle-earth by manufacturing an army of Orcs and wargs in a mud pit just outside the Tower of Orthanc. She gushed with enthusiasm as she stated that querists followed the Tarot because of its amazing accuracy. I couldn’t quite follow what it was all about, but I left the seminar intrigued by the references to the Kabbalah, an esoteric school of thought dating back to early Judaism which defines the nature of the universe, the human being, and the purpose of existence.

You cannot see the future clearly, but you must stay on your chosen path; trust your intuition; at your darkest hour, you will find that you hold your own light; use your own light to overcome your fears; shedding light on your fears will propel you toward self-understanding, strength, and self-confidence; through this process, you will heal and move forward into happiness.

Whoa there. That seemed to hit the nail on the head. Not bad for an arbitrary pick.

The book went on to describe a mysteriously seductive moon, the darkest nights of the soul, and fears rising up within our sleep in the form of desperate wolves that stalk too close in the night while we lie vulnerable and defenseless. A cold shiver moved down my spine, and I had to turn on more hot water for the bath. Pick up that stick! the text urged, and I resolved that I would whack that wolf with whatever stick I could get my hands on.

This reminded me of a forgotten episode in the forest on a black moonless night in the Santa Cruz mountains. I was lying in my sleeping back under a canopy of dark redwoods and had just nodded off to sleep at midnight when I heard the scraping of hooves, like a deer fleeing a predator, followed by the scream of a mountain lion. I bolted upright, immediately awake, and listening with every nerve, wondering whether I had dreamed it. I heard a low growling, very close. I was gripped by the strongest, most fundamental fear I have ever known, certain that at the next moment I would feel the claws of the wild beast landing heavy upon my shaking chest. My trembling hand reached for a stick while my heart felt the helplessness of fighting off the lion’s snapping jaws and curved scimitar blades. I stood up in my sleeping bag, made myself as large as possible and screamed “NO!” in a loud guttural voice that reverberated through the redwood canyon, then grabbed my bag in my arms and moved quickly down the canyon and back to the organized camp where my boy scouts lie asleep in their tents, shouting “NO!” again every few seconds in case the cat was following me.

Pick up that stick, my Tarot card urged. Whack that fear on the snout. Deal with these monsters of the moon and keep making progress toward the light, which is just up ahead.

The week wore slowly on, my last at Apple. Johnny M reported that the water level in the bilge had not risen, and I made my plans for diagnosing the source of the leak and the failure of the bilge pump. The work week ended with a lively after-work going-away party, where I performed with a rock band formed with four other Apple colleagues just a few weeks earlier.

The leak turned out to be a failure of four screws connecting a galley pump to the seacock that moved water from the galley sink overboard. The pump was below the water line, so that meant that with the seacock open the pump remained full of seawater. The salt water gradually corroded the bronze screws that secured the pump to the hose, and with a modest amount of torque I was able to pull the pump completely off its intake hose, bringing in a spray of seawater. I ordered a new one online, it arrived a couple days later, and I installed it without any difficulties. Whack! The wolf felt the blow of my stick and backed off a little.

I unshipped the electric bilge pump and took it apart, immediately finding the problem — a small rivet holding a washer that held the outlet valve had sheered off. This had caused the pump to stop pumping, and as the water in the cabin rose higher and higher, it eventually reached the electric wire that connected the pump to the float switch in the bilge, causing the wire to short out and melt down the bus connector. Pamela has a good supply of spare parts, including a rebuild kit for the electric bilge pump, and a few hours later I had the pump rebuilt with new values and diaphragm.

I replaced the melted bus connector, and acting on Johnny M’s advice, installed the new connector in a dry cabinet outside of the sloshing bilge. I started up the rebuilt pumped and listened with satisfaction as it purred, pumping out ten gallons of bilge water in a half a minute. Thump! The wolf howled in pain and retreated into the bush.

“Dennis, this is Dr. Shinghal” came the voice over the telephone. “I have the results of your biopsy.” When you’re on a boat, the phone always rings when you’re hanging upside down with your head stuck in a lazarette (a storage locker).

“Hold on, Dr. Shinghal, just a moment as I get my head out of this lazarette. I’m flushing Pamela’s water tanks clean.”

“Yes, that’s important,” he said. It sounded odd. Whether I had cancer or not was important. If I did have cancer, who cared about clean water tanks?

Did I really want to know the results of the test I had done a few days earlier, removing bits of tissue from my prostate to look for signs for cancer?

“Your results were negative — no cancer. This is the kind of call a doctor likes to make.” I would still need surgery to reduce the size of the prostate, but at least I didn’t have to worry any more about cancer. Thud! The wolf howled once more and ran away.

“Time to choose another card,” announced Pam as I soaked once again in the relaxing bath she prepared for me.

“Are you sure I should have another card read?” I asked. “The last card was pretty good. What if I get the wrong one this time?”

“It doesn’t work like that. Pick one.”

I selected again from the middle of the deck, again without any premonition of what I was choosing.

“Wow! Ten of Earth, the Great Work. That’s really good.”

“Really? What is it about?”

She read the description from Eakins’ book. It explained that my life was now moving with a wonderful rhythm, with a sense of order, balance, and harmony. I was now realizing a new kind of wealth based on the spirit. You have learned so much, now is the time to put what you know into words or other art forms in order to communicate it to others; you have long been a student, but you are a great teacher as well; following the spiritual path is the greatest of all your works.

I liked the sound of these words. Could this be true?

I was cycling from light-hearted elation, feeling the freedom of life without deadlines, to fear and worry about the financial prospects of life without deadlines. The word “retirement”, a really bad word, kept coming up. It tightened my stomach. It signifies a gray-beard stooped and shuffling in a meaningless direction with time and money running out. The word “sabbatical” is no better. It conjures up the security of returning to a significant position after you recharge your batteries. I don’t have batteries, and there’s no corporation out there waiting to take me back.

What shall I do today, or this week, or next week? Each step on the path is of far greater importance than where I’m going. I realized that in a single moment I can become centered, imagining the Great Work, feeling my feet on the path. This was true liberation. I was beginning the journey homeward.

It was time to stop thinking about materialism. I was now on sacred ground, beyond materialism, beyond the anxieties of material gain and loss. It was time to play my guitar, to write my story, to take Little Bear on long walks, and to say kind words to Pam. In my hand were all the tools to create.

You have learned that you can bring your ideas into manifestation. You can teach these ideas. It is clearly time for you to create newness: to use all your resources to do your part to re-new and to re-enchant your world.

There would always be mechanical breakdowns, and I would simply work my way through them until I reached the state where systems were whole and complete once again. Each fix brings an enormous uptick in confidence. I don’t need to worry anymore about what to do when the toilet breaks, or the refrigerator compressor stops running, or the wind generator stops making electricity, or the diesel gets air in the fuel line, or the bilge pump fails. I’ve been through each of these breakdowns and fixes, and Pamela’s seemingly complex systems are becoming gradually de-mystified. The point is not to be afraid of these eventualities, but to experience and learn from each of them in turn, for they are nothing more than waypoints along the path.

Bath time once again. I lounged back into the warmth and felt the slipperiness of the borax on my skin. My hands were full of nicks and abrasions from the recent repair and maintenance jobs on the boat, and the hydrogen peroxide in the bath made them tingle.

“Do you want to pick another Tarot card?” asked Pam.

“Certainly not — I just picked the Ten of Earth a few days ago. It’s not time to have another reading, it’s too soon.”

“It’s OK. You can have a reading each day if you want.”

“How does that work? Besides, I just drew two good cards. Suppose the next one is a dud. Suppose it has nothing to do with me and I lose my confidence in it; or maybe its a symbol of death or something bad like that.”

“It doesn’t work that way. Here, cut the deck and take a card.”

This time I selected the card with great deliberation. I did not want to pick a bad card. Selecting from the middle of the deck was too obvious, and no one would select the cards at the very edge, so perhaps I should take one from slightly near the left end, about a quarter of the way … my analytical mind need some kind of rationale.

“Oh! The Hanged Man.”

Oh no! It happened. I drew the card of death and eternal damnation. I blew it, my good luck had run out, or the cards had somehow confused me with someone else.

“It’s not what you think,” Pam attempted to reassure me. “Listen.”

It is time to retreat, withdraw and surrender to quietude; when the internal waters are stilled, you can see and hear your deep eternal self which is your own truth; your glorious nature is revealed when the clear waters of your mind cease to be disturbed by rippling thoughts; this is a time of voluntary withdrawal.

The Hanged Man is not being hanged from a tree, he is letting go. He is voluntarily withdrawing to go inside himself, going deep. Quieting his mind. He will emerge later in a more highly evolved state.

How this did ring true! Now that I was no longer working for a living I was determined to spend more time in reflection and meditation. I would withdraw from my previous work-a-day life, retreat to the woods or the sea, and descend into deep introspection.

I would sit for long hours on the bow of my sailboat, quieting my mind while I stared out at the endless sea ahead.

BVI and the Obscene Santa

To get a good feel of what its like to go cruising in a sailboat, head out to the British Virgin Islands and charter a boat from The Moorings. Christmas is the best time to go, for the trade winds are strong and constant, the weather is warm and perfect, and the islands are festive. You will be hooked. You will definitely come back or spend the rest of your life longing to go back.

We were back. The previous Christmas we had been newbies, neophytes, apprentices, greenhorns, nearly lubbers. Now we were experienced and we knew the ropes. We knew how to handle a 40-footer in the boisterous Christmas Winds of the Drake Channel. Last year we had discovered the Bight at Norman Island and the William Thornton with the Obscene Santa, but we had been reluctant to sail as far as Jost Van Dyke or the North Sound. This year would be different. We would actually meet Foxy.

And so it was with my new found confidence that I guided our ship out of the Moorings docks at Road Town and straight into shoal water. We got stuck in the mud not but four boat lengths from the dock. Sure enough, there was the green channel marker right there in front of us and we were on the wrong side of it. It was a near perfect grounding — four and a half feet of water at high tide. That means the keel was buried a foot and half and the tide was slowly going out, making the water more shallow by the minute.

Red right returning. So you want the red marker on your right when you’re coming back into the harbor, and the green on your left. So run this backward, and the green should be on your right.

This is the beauty of chartering a boat. You make silly mistakes on a boat with a limited insurance deductible, then play the mistakes back in your mind to make a permanent imprint. You recall all the channel marker rules from the sailing courses you’ve taken, but without the imprint they don’t register in real time when you’re out there sailing; and thus the mistake is made, and then the imprint is scored into the cerebral penduncle, and now you’re actually learning real seamanship.

The beauty of sailing on the San Francisco Bay is that you learn soon enough how to deal with a grounding. I recalled the time I had the Fohn, a C&C 40, stuck in a mudbank directly in front of the Corinthian Yacht Club in Tiburon. Close enough for the salts at the bar to enjoy the spectacle through the huge picture window, with the cityfront of San Francisco providing a dramatic backdrop for the sailing vessel with all sails full yet apparently not moving. I dropped the jib and mainsail and ordered Brian, Marc, and Vic out onto the boom, and the Fohn heeled over 20 degrees giving the keel some room. Brian had the worst of it, straddling at the farthest outboard point, when I revved the engine to 3000 rpm and began criss-crossing my way out of the mudflats. He howled like a cowboy, or was it the shrill cry of a school girl? as the boom came gibing about in wild fashion while the Fohn broke free. I fell to the cockpit sole laughing and could not get up.

I knew I could never convince Pam, Lindsay, and Julian to hike out on the boom like Brian, Marc, and Vic. So I applied all the available torque the diesel could provide and began the same criss-crossing, rocking technique. It worked and the boat popped back into the channel while I released one hand from the wheel to pat myself on my own back. Another imprint was scored, and seamanship prevailed.

We eased into the Drake Channel and felt our first gust of the Christmas Winds. The boat heeled a few degrees, and then I recalled in horror that I had not properly flushed the head. The bowl was good and full when we pulled out of the dock, for I could not flush it in the harbor. I had made a mental note to flush it when we reached open water in the channel. Somewhere in the process that mental note got pushed down the stack. Another penduncle post-it note gone missing. I jumped down the companionway and into the head, and sure enough there it was, a great stinky mess dripping onto the sole. The towels drying on the rack had of course fallen down into it. I partially swooned cleaning it up.

From your sailing courses you learn to wear your gloves when handling a line, and to always make sure a line under load is secure. I released the jib furling line to let out the sail but failed to wrap the bitter end around a cleat. The Christmas Winds caught the sail and it came flying out as the furling line ran out wildly and cut a crease in my ungloved hands and burned the skin off three fingers.

I was scoring imprints now at a prodigious rate. “Calamity mistake number three,” I noted. Three calamities and we were yet to actually sail the boat.

We sailed across the channel to Cooper Island. We were handling the boat properly now and the sailing was good as the wind freshened up to 20 knots. The mooring field at Cooper Island was mostly full as the smart cruisers had grabbed a mooring before the afternoon rush. We found a couple moorings still available at the farthest points out and made a plan of attack. The NE trades were fairly howling now, and the northern point of Cooper Island was causing a wind sheer that increased the velocity to 25 or 30 knots. We approached the mooring but as we reached it and backed down to stop the boat’s way the wind blew the bow off in a direction away from the mooring. No problem, I told the crew, we’ll just try it again.

And so on for the second attempt. The bow was blown off, and there was not sufficient time for Lindsay to get hold of the mooring pennant before the boat began sailing away from the mooring ball at speed.

And so on for the third, fourth, and fifth attempts. Pam, Lindsay, and Julian were all offering passionate advice on how to steer the boat. Each time one of them would grab the pennant the boat would arc away, and with only a boat hook to pull the 20,000 pound sailboat back to the mooring ball the simple physics of the matter overcame all Herculean attempts at raw strength. On one of the attempts we managed to wrap a mooring line around the lifeline, nearly bending a stanchion with the weight of the boat before getting the line free. On another attempt we were able to hook the pennant and then secure the mooring line to a cleat, only to find the line wrapped around the keel and pulling the boat amidships up to the mooring. The crew nearly mutinied when I insisted that we release the line and try again. The verbal assaults were flying now from bow to cockpit and back, and even the 30-knot gusts could not silence the insults and oaths.

Now we had all agreed that on this trip to BVI we would learn how to take up a mooring without raising our voices, as we noticed that the most experienced cruisers were capable of. All this was tossed over the side. There was not a cruiser moored at Cooper Island that afternoon that did not hear the various curses, shouts, and wailings from the boat trying to secure itself at the farthermost mooring.

These were gusts I had not yet experienced — great screaming williwas of katabatic squamish wind in a profound Venturi. And they seemed to blow hardest each time we stopped the boat precisely at the mooring ball.

I finally abandoned that particular mooring, not from want of trying, but because on the sixth pass I managed to drive over it with the prop in forward, thus cutting off the pennant line altogether. I was doing really well — not. I had terrified my crew, disturbed the tranquility of the anchorage, and deprived another sailor from using the now useless mooring ball.

After a dozen attempts we were finally settled and secure. Down in the cozy salon we ate our supper and listened to the howling of the wind without a care.

‘Round midnight the calamities started up again. I was lying in my bunk and thinking about all the strain on the mooring line. I should have set two lines. The wind was still whistling shrilly in the rigging, deck hardware was rattling everywhere, and the boat was arcing around in a wild restless motion. I went up on deck and secured a second line from a bow cleat through the mooring pennant and to the other bow cleat. As I made may way back to the cockpit I noticed the inflatable dinghy. It was inverted. The prop shaft of the outboard motor stood straight up as the outboard head served as a keel. Thankfully I had taken care to secure the gas tank with a line.

It wasn’t easy to right the dinghy, for when we lifted it it wanted to fly away like a kite. But we managed to do so and the salt water ran in rivulets from the outboard engine housing. We went back to our warm bunk feeling the security of the second mooring line and a sense of accomplishment.

The next morning the williwaws were still gushing past Cooper Island as we slipped the mooring and ran south on the six-foot swells. Down-island we ran, licking our wounds, broad-reaching down to Norman Island. We were anxious to get into the calm waters of The Bight. The dinghy also seemed anxious to get there, and surfed down the waves on our stern in a vain attempt to overtake us. Day Two was proving to be a marvelous day of glorious downwind sailing.

We were tied to a mooring in protected waters a couple of hours later. I dived over the side and inspected the prop, and sure enough there was the tangled mass of mooring pennant that I had severed at Cooper Island. I sawed away at it with a knife and then deposited the heap on the swim platform, where it managed to remain undisturbed for the next eight days.

With a few hand tools from the ship’s stores I jumped into the dinghy and proceeded to take apart the outboard engine head. I inspected and cleaned and dried, but did not prime the carburetor with gasoline. I pulled on the rope again and again, but the ignition would not ignite, and the mute sputtering told me it was time to call The Moorings. Pam had been telling me this for an hour or so, but of course I needed to prove that I could get the water out of the engine myself, or prove it not.

A rastaman appeared an hour later in a whaler with a couple of serious outboards behind. He inspected my half-disassembled engine and repeated some of the steps I had done. He also primed it with fresh gas. I offered him a beer as he sweated in the afternoon sun, for it seemed to me that all men should drink beer religiously in BVI. He declined, for rastamen do not drink, and accepted a cold Perrier.

“Good water,” he announced with a grin after having a taste.

Away he pulled on the starter cord, once, twice, thrice, and so on for about a minute, and then stopped and rested. I was sure that it would not start, for after my unsuccessful attempts and the attempts of the rastaman, surely the engine would never start again.

He rested a moment and had a long pull from the Perrier.

“It will start this time,” he declared. And with one final pull the engine roared back to life. And a moment later he was back in the whaler and roaring out of the mooring field and back into the channel.

With the dinghy in service we were now able to leave the boat. Pam and the boys and I jumped in and headed straight to the Willie T for lunch, a Painkiller, and a jump from the poop deck of this floating steel-hulled barge. This floating restaurant and bar is named after William Thornton, an eighteenth century polymath who was born in Jost Van Dyke from British Quakers who built the first sugar plantations in BVI. He left the islands at age five to be educated in Lancashire, became an teenage apprentice to a physician and apothecary, then a writer and painter, then a doctor, visited the US with a letter of introduction to Benjamin Franklin, visited Paris, won a competition for designing the new US Capital in 1793 with a design influenced by the Louvre and the Pantheon, and later was appointed by Thomas Jefferson to oversee the new US Patent Office.

In the bar on the upper deck we found that the Obscene Santa was still there. We discovered him the year before, on Christmas Eve, a plastic Santa doll above the bar that sported a shamefully ignominious spar that danced up and down with the movement of Santa’s hips. William Thornton’s mother, who he never saw from age five until he returned to BVI at age 27, would have fainted.

I was hell-bent on getting to Jost Van Dyke for New Year’s. Great Harbor, the small bight on the southern side of Jost Van Dyke, was home to Foxy’s, and every year hundreds of boats rafted up for a raucous New Year’s Eve celebration. In the months before leaving for BVI I had scoured every chart to determine how I could get to White Bay, a small anchorage just west of Great Harbor, in time to get a mooring before the sailing horde arrived. So early the next morning I slipped my lines and sailed past the Indians and through The Narrows to Jost Van Dyke. It was another morning of glorious sailing, as all mornings inevitably turn out to be in BVI.

We tied up in White Bay without any of the antics from Cooper Island. The crew were starting to get good at this. To actually tie to the mooring I had to wake up the boys. As teenagers, they are happiest when lying asleep in a bunk, at least until the sun had reached its noon zenith. We were starting to get into the groove of cruising, and shouting about a mooring seemed like a breach of equanimity. Something a lubber would do.

White Bay was white and pristine. On the shore our toes dug into the sandy floor of Ivan’s Stress-Free Bar. I imagined coming back to Ivan’s one day with my guitar and entertaining the sparse crowd with my folky originals and 60’s recreations with shades of blue, as I imagine in every tropical bar I enter. To sail a boat to a stress-free bar and play music until The End, this is a formula that explains existence. It organizes all philosophic thought from Pythagoras to James into a dialectic stew pot in which the theists, atheists, agnostics, epicureans, and fatalists congeal into consensus from the roux of wind, sun, and freedom.

Meanwhile, a half mile down the beach a cruise ship anchored and began dispatching a series of land-bound launches. In another hour there were a couple hundred people at the far end of the beach clogging up the Soggy Dollar Bar, another of Jost Van Dyke’s treasures, named by the currency offered by cruisers who swim to shore for an afternoon respite. From Ivan’s we walked down the beach and into the crowd, taking note of the sense of urgency of the well-dressed vacationers who chatted on cell phones on the beach. Feeling superior, for we had our own boat and thus ultimate control of destiny, we rode the dinghy back to our boat, then set off for Great Harbor and Foxy’s.

“This is an island dog,” proclaimed Foxy as he rocked on his restaurant veranda. He pointed to a sleeping black labrador at his feet.

“Oh?”

“Do you know why he’s an island dog?” Foxy questioned me.

“No sir … er … Mr. Foxy.”

“Because he’s black. He sits on his ass all day long. And he don’t know who his daddy is.” And with that he took another pull from his drink. It was four in the afternoon and he seemed serenely blitzed as he rocked away in his famous restaurant and bar tucked away in a corner of paradise. I felt I needed to catch up.

It was still a few days before New Years Eve. With all my planning I had managed to get to White Bay a full three days before New Year’s. I had to choose between the great New Year’s Eve party at Foxy’s and the raft-up of hundreds of boats, against the prospects of sailing on to the north. Once again we slipped our lines and set sail for more adventures.

For onward lie The Baths of Virgin Gorda, the expansive North Sound, Trellis Bay with its artists burning great caged effigies on New Year’s Eve, and not least — back to Norman Island for one last Painkiller on the Willie T with the Obscene Santa.

A Sneak Preview of Paradise

On December 29, 1810, Charles Fourier sat in his small shop and huddled by the little coal heater in the corner to keep warm. Another winter storm was beginning to blow down the empty back alleys of Paris’ Latin Quarter, and the myriad couples who had so gayly strolled these alleys on Christmas Eve, clutching tightly to each other through their long woolen coats, were no longer here. What were the chances that someone would come to the shop today to purchase his handbook of utopian instructions?

His thoughts were dark on this gray afternoon. In the two years since he had published his first work, The Social Destiny of Man, he had attracted some attention, but very little income as a social scientist. Why should anyone buy his handbook? Anyone could fabricate a story about Paradise.

A garden called Eden, he mused, where everything a man needs is within his grasp, vine-ripened and ready for his plucking. Save for one particular fruit at the dead center of the garden, which the man must never eat.

“There is always that one fruit,” he said aloud. That one thing that brings discomfort even in the very center of Paradise.

One man will find Paradise while sitting under a tree, while another man will study the writings of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle to seek a formula from the ancients. Charles Fourier had read these, and of course Bacon, Spinoza, and Voltaire. Their books were stacked neatly in the corners of his shop, never gathering dust, for he reached for them habitually during his long afternoons of thinking, wondering, and inventing.

And then there was Kant, who reasoned that space and time were not things in themselves, but were formed by our intuitions and perceptions. The lines of Charles Fourier’s mouth turned downward as he tried to make sense of Kant. Like light through a prism that changes its shape and colors depending on the perspective of the eye, the defining characteristics of Paradise change based on the perspective of the viewer.

So Paradise was not really Paradise, but only our perception of Paradise. And that discomfort at the center of Paradise — was that also an invention of our human perception, and if so, couldn’t we simply decide to un-invent it and let it fade from existence?

Charles Fourier’s thoughts were interrupted by a blast of arctic air through the doorway of the petite shop, sending his papers scattering across the dimly lit room like snowflakes ripping down the rue de la Harpe. He clutched in vain at the flying sheets, then resigned himself to the disorder as his good friend Luc bounded into the shop behind the wintry blast.

“Bonjour, mon amie! And how is the business of utopia today?”

“Comme ci, comme ça. Comme d’habitude,” he offered with a trace of a grin, for Luc was always full of energy and his boyish enthusiasm was infectious even in December. “Not many visitors to the shop on such a freezing day, but you know how it is — I must write nonetheless. And how is the boulangerie and the business of baking bread?”

“It is the same each day — the good people of Paris need their daily bread and I am here to pull it fresh from the oven each morning for them. It does not change.” His bright eyes surveyed the little room with the stacks of books in each corner. Luc was not much of a reader, but he knew these books well from his long conversations with Charles Fourier as they strolled the boulevards of nineteenth century Paris on the afternoons when it did not rain or snow.

“It does not change, Luc, but in its constancy and simplicity it forms the essential ingredient of any utopian society.”

Luc laughed easily and grasped his friend by the arm. “Oh Charles, you are such the thinker. Come! Let’s walk to the cafe and warm ourselves with an absinthe, all the better to battle this winter storm.”

They bent their heads to the northerly as they made their way through the labyrinthine streets. “Have you any more news of the Pacific islands reported by Bougainville?” shouted Luc through the wind.

“Oh yes! The reports from the English describe a nation of innocents. They live in the natural realm and seem to be very happy.”

“Is there an apple?” Luc winked.

“Of course, dear Luc. There is always an apple in Paradise.”

“Well continue to study and to write about it, for one day you will be very famous throughout Europe.”

On that freezing winter day Charles Fourier could not know that he would influence many of the greatest philosophers and social scientists who would follow: the likes of Emerson, Thoreau, and Marx. Although Marx would criticize him as being “too utopian.”

Can one be too utopian?

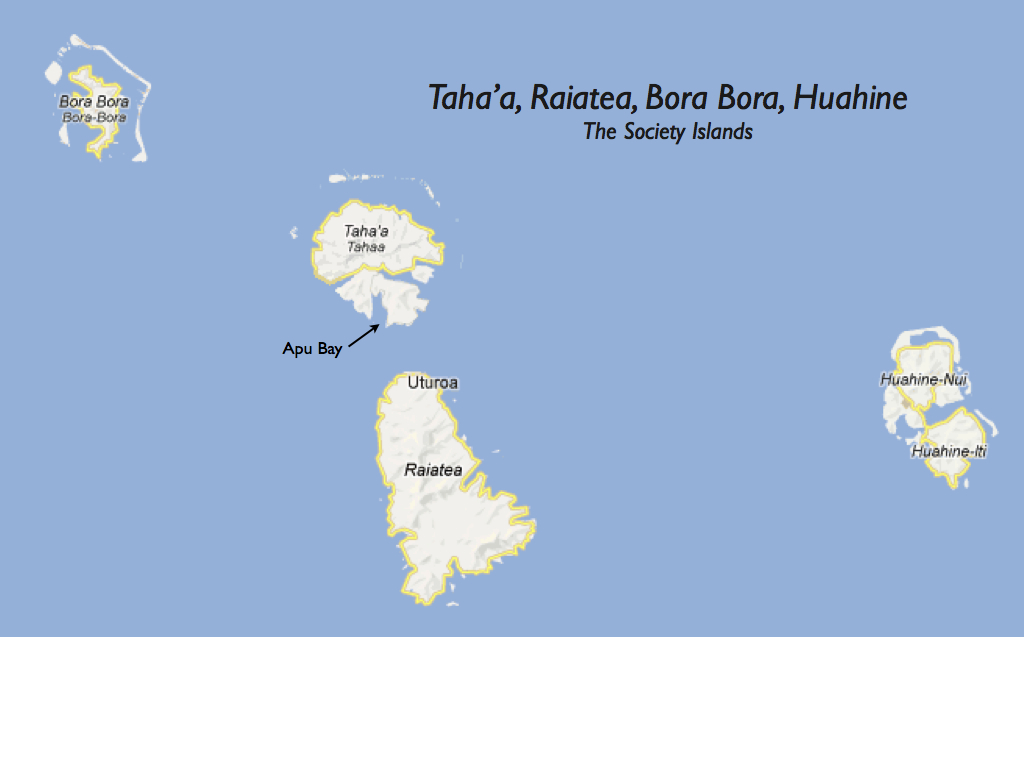

On December 29, 2010, I awoke to a still summer morning in the protected Apu bay of Taha’a on French Polynesia. The sun was beginning to rise on the horizon just viewable across the open lagoon between Taha’a and Raiatea, but its early rays had not yet penetrated the bay itself. Coconut palms grew in a dense fringe along the shore of the bay. The north easterly carried the distinctive scent of vanilla from the lush inland valley. Exactly 200 years after Charles Fourier’s wintry day, I was seeking freshly baked French baguettes in Paradise.

From the transom of my sailboat I stepped into the dinghy without spilling any of the hot sweet coffee that I held tightly in my left hand. I started the outboard with a single pull, then released the lines and motored silently across the little bay, now calm after the squally night. Yesterday the rain had exploded from a cloudburst in the afternoon, and I had stood in the cockpit of the sailboat naked and enjoying the warm shower. The rain had continued in drizzles and squalls throughout the night, and now the day was dawning with only a few clouds with the freshness one feels after a long, warm rinse.

The dinghy glided toward a small pier near the point. I imagined my approach and mentally calculated the deft movements of my right hand on the throttle of the outboard motor, gauging the acceleration and steering direction that would manipulate the prop to bring me alongside the pier without a bump or a scrape.

The day before I had come to the pier with too much speed, and the rubber boat had bounced hard off the pier and flung me sideways, while the motor sputtered out and the wind blew the dinghy back out into the bay. I didn’t want to repeat that performance, and I didn’t want to spill the coffee in my left hand.

Today would be different, I told myself, as each day in Paradise turns out to be. The morning tide was lower now, so the pier stood a little higher in the water. I aimed for the edge of the pier and tried to slow down, but the bow of the dinghy thrust itself under the overhang of the pier.

It was tight fit, just enough to let the bow go under the pier and tight enough to keep it there. The dinghy swung hard alongside while the port gunwhale bumped along under the deck of the pier and took me along with it, bumping and scraping in agitated sympathy. Coffee went everywhere. I fell back feet over head and wrapped myself up in the outboard motor. Oh well, must keep practicing.

At 6:00 a.m. the Taravana Yacht Club bar was empty and there was no one there to enjoy my collision with the pier. Indeed, there would be no one at the bar until I came back later in the afternoon for a pre-sundowner, for it was summer, the off-season for tourism in Tahiti. As if Paradise had an off-season. I secured the dinghy, cleaned up myself, and bailed coffee out of the bilge. As the dinghy rested perfectly alongside the pier I made a plan to perfect that landing by attempting it 10,000 more times in Paradise before The End. It was a good plan.

The Taravana Yacht Club is not really a yacht club. It’s an open-air bar on a little beach at the point of Apu Bay, and Richard the owner lets me tie my boat to a mooring each day if I promise to come to bar each afternoon and have a drink or have his lovely wife Lovina make us poisson cru for dinner.

Richard came to Polynesia from America over thirty years ago sailing a small boat. Like Bernard Moitissier and Paul Gauguin before him, he decided never to leave. He had lots of stories to tell, such as the times he had taken Jimmy Buffet out for sport fishing in the blue water beyond the reef. He now owned the Taravana bar and operated its restaurant with Lovina who is part-French and part-Tahitian and spoke French with me.

I passed through the open bar and out the back door. The dogs in the huts behind were not up yet. They allowed me to pass through the coconut grove and along the hibiscus trail without any sound save the refrain of the song in my head, the chorus of a new song I was composing. In Paradise, you have the space and time to write a song or a story. You don’t have to work very hard to practice your art, for the natural opening of the heart, the mind, and the senses provides you with unlimited space, like an endless sea.

I found the island road and passed the pearl farm. The day before, when I had visited the pearl farm, the elderly madam who lived there told me her husband had passed away the year before. She didn’t know what to do with the pearl farm. She showed me her striking black pearls spread about on tables on her verandah, a verandah which surrounded the house on three sides and offered views of Paradise through the coconut palms as the gentle trades blew a refreshing breeze into the room.

Any true Paradise has pearls, of course; for is Heaven not entered by pearly gates guarded by St. Peter himself?

On the island road I found a coconut that had just fallen from the tree. It was green and ripe, with its husk broken apart by the fall and ready for me to extend my hand for the taking of the sweet coconut meat. From a crack in the center nut I drank up the milky juice. Past the line of banana trees was the small white building, plain and non-descript in itself but exactly as Richard had described to me.

The white building looked like someone’s house, but without windows, and I was a bit shy of approaching. There was no sign on the building. Around the side I found a large open door. Inside were three island men moving racks of dough into a room-sized oven. They had been up since 4:30 a.m. to begin their baking. Each day they prepared bread and sold it to the supermarkets and resorts on Raiatea and Bora Bora.

I gestured for a baguette that had just been taken from the oven and was cooling on a rack. I smiled broadly as one of the men handed me the loaf and took my 50 centimes in his brown hand. He was elderly and serious and did not return my smile, for this was work, and for him the day was no different than the one before or after. In the constancy and simplicity I thought of Charles Fourier.

A younger man spoke English quite well and grinned in a friendly way when I asked him about the round loaves he had just taken from the oven.

“Coconut bread,” he replied.

Voilà — the voluptuous ingredient that makes bread from Paradise unlike no other bread. “Is it sweet?” I wondered.

“Oh yes. We put the meat of the coconut in it.”

“Can I buy one?” I asked him.

He frowned. “I will have to check. They are for a party and we do not normally have them.”

He walked across the narrow island road to a house, then came back a moment later with the wonderful news. “You can have just one.”

“How much is it?”

“It is 200 francs CPF. Be careful. Don’t crush it.”

About two dollars for a fresh-baked circular loaf of coconut bread, crisp and brown on the outside and steamy white inside. I tried to remember the French word for “crush” and couldn’t think of it. I admired the young man’s English which was much better than my French.

“Quelle bonne journée,” I ventured, and with my baguette and coconut loaf under my arm I returned to the grove past the pearl farm and past the dogs who had by now awoken and gave me short barks with half-wagging tails as they admired the aroma of the freshly baked bread. I imagined a day when I would return to Taha’a and stay for more than just a few days, bringing doggie treats for them, and I would teach them to recognize me by the treats accompanied by the special whistle that I always use when feeding my puppy Little Bear.

Through the open bar and out to the pier, where the dinghy waited to humiliate me once again. I maneuvered dexterously from the pier, this time in control even with the baguette, the coffee cup, and the coconut bread which I did not crush. I throttled lightly across the bay and then eased back as I neared the sailboat. I timed the touch of the dinghy’s bow against the swim platform with the gentle swell of the lagoon in the light morning air and set down the coffee cup and the bread upon the platform one-handled while controlling the dinghy, the outboard, and the bow line. A minute vortex in the history of time, in which all good things can happen at once to a man in Paradise.

I heard another outboard motor close by and waved to my neighbors, the young couple I had seen the night before at the Taravana bar, when Richard was explaining to the young lady that the mahi-mahi was basted in shoyu. From the careful way he was explaining this I imagined that the young woman was intolerant to soy, or gluten, or salt. I tried to imagine being intolerant to French cooking in Paradise. It didn’t seem like a happy state.

“Is there any left?” the young man asked me as he gestured at the baguette. My stomach tightened, almost imperceptibly. I imagined the worry of running out of fresh island-baked bread. Of lining up to get while the getting was good, of racing to be at the head of the line. Of economic constraint and the pushing and shoving that accompanies it. The apple emerging once again, turning Paradise suddenly into hell.

As I turned my attention to the tiny sensation in my stomach I realized that by noticing such barely perceptible feelings from within I was making progress in my daily pursuit of mindfulness. “Worry”, I labelled it, and having been labelled it began to fade like a cloud over the lagoon.

I turned to the young man and smiled warmly. “Yes,” I assured him. “There are many and plenty.”

Pamela Goes to Sea

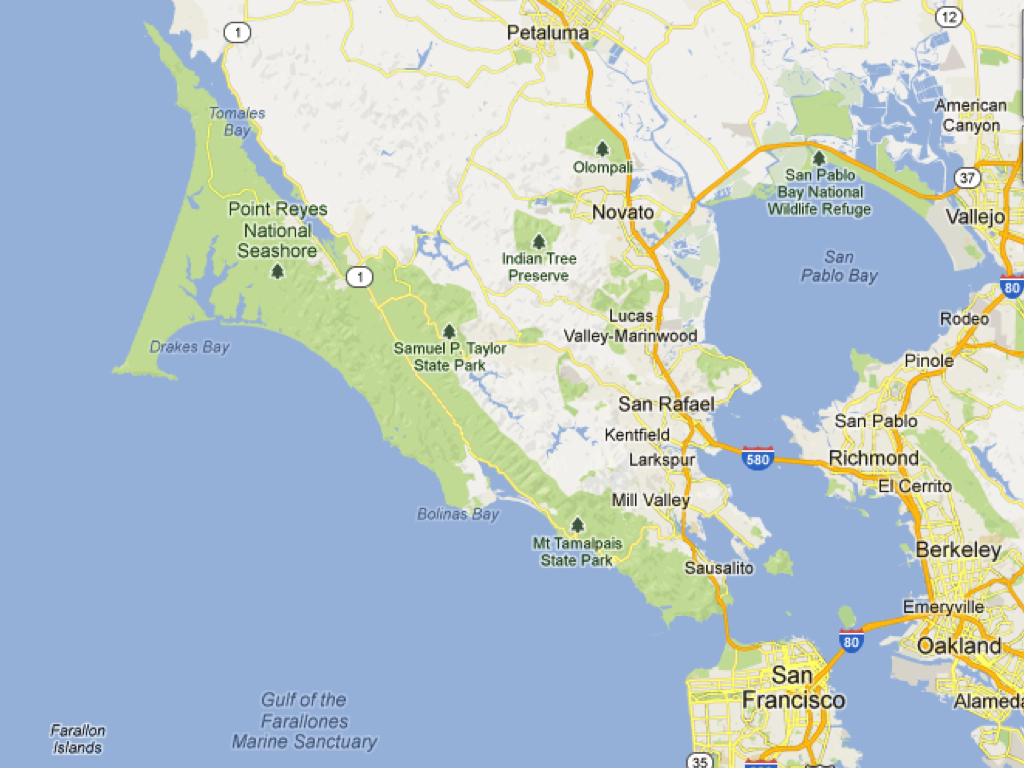

With her new christening as Pamela and brightly varnished teak, and my restless hands hands longing to trim her sheets, it was time to take my cutter-rigged Crealock 37 on my first single-handed ocean sea trial, an overnight sail from San Francisco bay through the Golden Gate to desolate Drakes Bay on the beautiful Point Reyes peninsula. Drakes Bay seemed like a good challenge, especially for me single-handing. There is something ominous about taking a boat outside the protected waters of the bay and into the rollicking Pacific rollers along a rocky lee shore. Often foggy, the cape of Point Reyes has claimed literally hundreds of ships in the past 400 years of nautical history. The Gate is more than a portal from the world’s most lovely city to the blue ocean beyond; it is a milestone in the life of a sailor. Turn left and you fly downwind and surf the rising swells. Turn right and you take them hard on the bow while you battle the 20-knot winds head on. Go straight and you sail into the sunset and on to Hawaii, beam-reaching your way to the trade winds that enabled the Age of Discovery.

Drakes Bay lies about 30 miles past the Golden Gate, or about 40 nautical miles when tacking against the prevailing north-westerlies. It is a protected anchorage in typical conditions, but must be avoided when the winds clock to the south to announce the coming of a winter storm.

Point Reyes is a triangle jutting out from the California mainland, and is believed to have moved up from Southern California millions of years ago. It is part of the Pacific tectonic plate under the great ocean, totally separate from the North American plate which forms the mainland. It is separated from the mainland by the San Andreas fault, which forms the beautiful Olema valley from Tomales Bay on the northern end to Bolinas Bay south. On its southern end begins a graceful curve to the west ending in a dramatic rocky cape a few miles out to sea.

I found myself approaching this cape in complete darkness and thick fog and screaming along at 6 knots.

The day had been sunny with great visibility and was expected to reach 70 degrees in San Francisco, unusual for early March. It was a Monday morning and very few boats were out. Everyone else was trying to get to work. I passed under them on the Bay Bridge. While they stalled in their cars Pamela caught a light northerly and picked up her bows in anticipation of a great adventure brewing. She sailed easily along the city front and pointed to the Golden Gate and the sea beyond. How happy I was! Single-handing my own sailboat on a gorgeous Spring morning, light winds on a close reach, catching a strong 4-knot ebb tide to sweep me through the Golden Gate. And to adventure!

The seas beyond the Gate were very gentle. A swell began as soon I passed the Golden Gate Bridge, but ever so mild, one to two feet. I brought my guitar up on deck and sang my ocean song. I delighted in the warm sunlight.

The seas picked up a bit as I moved out beyond Point Bonita. It was time to put the guitar away. I was apprehensive about getting sea sick, as I had once done off of Point Bonita. It was a sailboat race to Drakes Bay several years ago with my buddy Bill and his little ship Zora. For several months I had been pressuring Bill to take Zora out into the ocean, and he gradually agreed, although without great enthusiasm, and registered for the Drakes Bay Race sponsored by the Corinthian Yacht Club. On that morning I glanced through the binoculars at the Point Bonita lighthouse just as the swells were beginning, when suddenly my stomach gave a lurch and I knew I would soon be sick. A short while later I was nearly lifeless, sitting limp in the cockpit and not moving — not joking, not laughing, not helping sail the boat, and not preparing lunch. And what a lunch I had planned! For weeks leading up to the race I had planned what wonderful food I would prepare for the crew. Yet there I was, unable to get up and go down into the galley to make anything while the crew sat hungry as the day wore on. All my talk about sailing across the Pacific! What complete crap — here I was absolutely immobile about a mile into the ocean. One can plan, one can boast, read all the literature there is about the sea, and wax poetic about the ways of the sea; and in a single instant be claimed by the sea.

Now some would believe that this very point proves that planning, boasting, reading, and waxing are ridiculous. The sea will eventually get you, so stop all this baloney. Take care, be serious, put down the guitar and stop singing such naive songs about Mother Ocean. I say the opposite: since the sea is going to get you, you had best plan, prepare, read, and sing as many naive songs as you can in your life time.

On that day with Bill and Zora, I up-chucked my breakfast into the sea, moped about for a few hours feeling like a foolish boy, and then staggered to my feet and announced that I would make lunch or die in the attempt. The crew ate well after all.

The memory of that day so many years before brought a twinge of anxiety as the swells began to build. I didn’t think I would get sick this time, and if I did, oh well — in the words of Joshua Slocum, the first solo circumnavigator, “What of that?”

I heard a sudden gasp of air. From the blowhole of a mammal in the water — a whale? Something black out of the corner of my eye was buried quickly into the sea. I looked around and saw nothing. A half a minute later I heard it again, this time off the stern to starboard. It was a dolphin. A black dolphin, following me along outside the Golden Gate. He followed me a mile or so and I was happy to see him surface each time, until he surfaced no more.

I spied the bluffs of Drakes Bay 30 miles away. At first it looked like an island, for the plain leading to the cape looks rather low from that angle, especially as the Marin headlands loom in the foreground. I don’t recall an island formation like the Farallones just north of the Farallones, but sometimes you learn of something like this, like the fact that there is an island 27 miles off the coast of California beyond the Golden Gate. And when you first hear of it, you think, “Oh, interesting. I suppose there could be an island off the coast.” And so maybe there actually were islands beyond the Farallones. I checked my chart two or three times to make sure there was no such island.

When you first see your destination on a long backpacking trip, you think it is something else, something far distant. You find hills or ranges between you and the destination and you imagine that they are the destination, and the false destination is actually something way further off, miles farther. When you think you have reached the top of a ridge or a mountain, you find that you have reached just a shoulder. And onward is the summit. And you gulp.

So it was with Drakes Bay. The island so far off was Drakes Bay, and it seem a hell of long way off, and the wind was coming straight from that direction and was picking up a bit. Some fog was forming in a bank a little way off from the cape.

Pamela made steady progress past the most spectacular coastal scenery in all of California. I tacked toward land and sailed in close to the shore to see the sheer bluffs and sea caves. The forests of Marin are untouched and have some of the very oldest of trees, the Muir Redwoods. When I could clearly make out the surf line and see the pounding waves on the rocks, I watched for a bit then tacked to seaward.

“All hands, prepare to come about! Ready about?”

“Ready on port.”

“Ready starboard.”

“Helm’s alee!”

What an adventure it is to tack a boat by yourself. You never have to wait for someone to say, “Ready”, nor remind crew to call forth with such responses to issued commands. You simply shout, “Ready!”, or perhaps you feel like a bugger and you delay shouting Ready just to see if the skipper will get pissed at you. And you turn the helm and let go the working jib sheet and grab the lazy sheet to take in slack, and pull hard around the winch, and check-swing the helm to stabilize the turn, then switch back on the autopilot while heaving the sheet one last time before resorting to grinding. All in 30 seconds and without losing two knots.

On the seaward tack I could see the Farallones. Only fifteen miles off, they seemed small and distant. The seaward tack was the slow tack, doing only about 4 knots. The seas were building to white caps and were hitting harder on the starboard bow on the seaward tack. The shore bound tack was faster and more comfortable, easily 6 knots. It was glorious sailing.

A moon came rising in the eastern sky, prematurely it seemed. Meanwhile the sun began to settle its day-long flight. Any moon flying over any sea is utopia, and all sunsets added together make nirvana. This sunset melted softly into the fog bank offshore and invited me to follow. Not yet. That’s coming. Be patient.

I was hoping for a bit more sun before ending this day, as I had another hour to go before reaching Drakes Bay. Happy to have a full moon, though. Not long after the sunset the fog moved in and obscured the cape. In a short while it was completely dark and with near-zero visibility. The moon was still there, and to seaward a few stars shining brightly enough to pierce the fog bank.

I thought of Pam. I wanted her there with me but she would have freaked out with the waves, darkness, and fog. She has yet to learn to use Pamela’s instruments and to trust that they will guide you safely into the anchorage. The radar showed the cape and some obstruction on the north west part of the bay, while the chart showed water depth and the AIS (Automatic Identification System) indicated whether there were any commercial boats, like fisherman, out and about or anchored in the bay. I was pretty sure there were no other sailboats about. No one is crazy enough to go to Drakes Bay for no reason.

Nothing on the seven seas works quite as well as Pamela’s windlass, a sturdy bronze Muir. We plopped down the 45-pounder in 28 feet of water and let out 150 feet of chain. She wavered not a bit after that, but was happy to bed down for the night. The chart plotter showed how far I was from the beach, and as I rose to check it four times during the night it always showed about 890 feet to the closest depth line.

That night and the following night were spent listening to all the mysterious sounds about the ship, especially the rigging tossed by the whistling winds. Periodically I would rouse myself from my light sleep, don my foulies and clamber up on deck to see what I could do about lines whacking on the mast. I tied a web of preventers, knots, and bungies from the various halyards and sheets to the spreaders and stays, but there would always remain a single mystery line a-whacking away. Standing at the mast in a light gale I struggled to perceive the mystery line; when I returned to my bunk it would start up again, bright and true. It had a mind of its own, and a song to sing; who am I to attempt to control it? I’d best enjoy the song.

At last I would fall into deep sleep, as is inevitable even in a sleep-deprived environment. In deep REM sleep I had dreams, including nightmares about falling overboard. In one such dream I found myself in the water behind the boat. Jib sheets were streaming in the breeze aft of the boat but I was unable to reach them. Pam was on deck, and she was in a fair panic. She did not know what to do. I yelled, “Turn around and get me!” while off she and Pamela sailed.

In another dream I found myself in mid-air above the cockpit. You have a feeling of complete weightlessness when you are thrown into the air, as on a trampoline. I felt myself in this state, moving upward, and was immediately cognizant that I’d been thrown high into the air from some amazing violent force against the ship and was still flying higher as Pamela sailed on. The feeling in the dream was incredibly real. At once I knew my fate. I thought to myself, “This is it! This is actually The End!” I imagined myself sinking into the deep while I was still high in the air. This dream seemed completely final, the dream to end all dreams. And yet dreams, like al things, must come to an end.

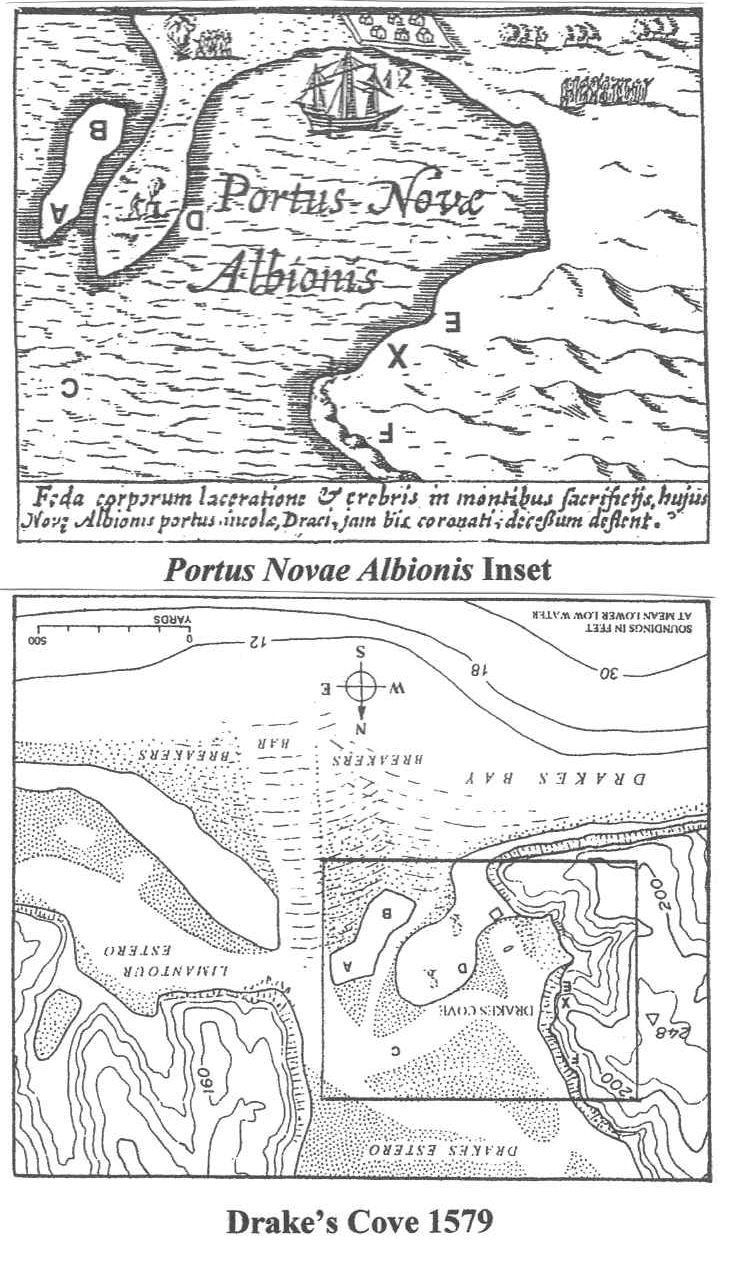

Sir Francis Drake completely missed the San Francisco Bay, but discovered the long crescent bay of Point Reyes in June of 1579, where he hauled The Golden Hinde onto the beach for repairs before striking for the Spice Islands of Indonesia. When he returned to England three years later, Queen Elizabeth I ordered his ships log and journals to be considered as classified information, fearing King Philip of Spain would learn the position of Drake’s “safe harbor”. A hundred years later all of Drake’s records of his circumnavigation, including valuable logs, charts, and artifacts were destroyed forever when the palace containing them burnt to the ground. And so it is that the exact location of Drake’s landing has been hotly debated for a few hundred years. While there are numerous theories of landing sites other than Drake’s Bay, some arguing further up the California coast or Oregon or Washington, most historians think this was the actual bay because of descriptions of the Coast Miwok Indians, the white cliffs, and surprisingly, a particular pocket gopher which inhabits Point Reyes, clearly described in detail by Francis Pretty, a member of Drake’s party.

Drake named the place “Nova Albion”, meaning New England, possibly because of the white cliffs around the bay. Albion, or “the white”, was the Latin name for England and is a reference to the chalky white cliffs of Dover. Drake came here with a single ship, the Golden Hinde, for one of his ships had sunk while attempting to pass through the Straits of Magellan near Cape Horn, and another had to return to England for repairs. The Golden Hinde was carrying various treasures from several encounters with the Spanish on the journey north through South America. While England and Spain were not officially at war, Queen Elizabeth I ordered Drake to harass the Spanish towns and ships along the Pacific coast. Not quite a hundred years had passed since Columbus’ famous discovery, yet the Spanish had been very busy with gold and silver exploits in Peru. Like Henry Morgan in the 17th century, Drake established himself as a daring and successful buccaneer against the Spanish Main and sacked Nombre de Dios on the isthmus of Panama a few years earlier by capturing a mule train laden with silver from Peru. What distinguished Drake as a buccaneer, and not an outright pirate, where the “letters of marque” he carried from the Queen, essentially royal permission to make war on the Spanish whenever convenient. The Spanish galleons were a magnet to enterprising sailors such as Drake and Morgan.

When the Golden Hinde landed in Drake’s Bay, it is likely that she carried Peruvian gold and silver worth over $40M today. This includes 80 pounds of gold and 26 tons of silver taken from the Spanish galleon Cagafuego, Drake’s greatest prize ever, captured off the coast of Ecuador about three months before arriving at Nova Albion.

A few years after Drake, in 1595, Spanish commander Sebastian Rodriguez Cermeno earned the distinction of becoming the first of many documented shipwrecks at Point Reyes. His ship San Augustin was carrying exotic cargo from China to Mexico to be transported across Panama and on to Spain. He anchored in Drake’s Bay and was hit by a winter storm that sent San Augustin up onto the beach where she foundered and broke apart. In Two Years Before the Mast, Richard Henry Dana describes how his vessel in 1838 would always go several miles out to sea when a winter storm was approaching, which was clearly indicated by a southerly. Why Cermeno remained in the bay as the storm approached is a mystery, for the bay is entirely unprotected when a strong breeze kicks up from the south. Nonetheless, the Coast Miwok Indians that inhabited the area must have rejoiced in the bounty they received from the San Augustin, including porcelain from the Ming dynasty. Imagine the head of the tribe replacing his gopher skins with Chinese silks. While the ship and its cargo were lost to Cermeno, he managed to get 70 of his crew into a small open boat and sail for Mexico, reaching Acapulco two months later.