To get a good feel of what its like to go cruising in a sailboat, head out to the British Virgin Islands and charter a boat from The Moorings. Christmas is the best time to go, for the trade winds are strong and constant, the weather is warm and perfect, and the islands are festive. You will be hooked. You will definitely come back or spend the rest of your life longing to go back.

We were back. The previous Christmas we had been newbies, neophytes, apprentices, greenhorns, nearly lubbers. Now we were experienced and we knew the ropes. We knew how to handle a 40-footer in the boisterous Christmas Winds of the Drake Channel. Last year we had discovered the Bight at Norman Island and the William Thornton with the Obscene Santa, but we had been reluctant to sail as far as Jost Van Dyke or the North Sound. This year would be different. We would actually meet Foxy.

And so it was with my new found confidence that I guided our ship out of the Moorings docks at Road Town and straight into shoal water. We got stuck in the mud not but four boat lengths from the dock. Sure enough, there was the green channel marker right there in front of us and we were on the wrong side of it. It was a near perfect grounding — four and a half feet of water at high tide. That means the keel was buried a foot and half and the tide was slowly going out, making the water more shallow by the minute.

Red right returning. So you want the red marker on your right when you’re coming back into the harbor, and the green on your left. So run this backward, and the green should be on your right.

This is the beauty of chartering a boat. You make silly mistakes on a boat with a limited insurance deductible, then play the mistakes back in your mind to make a permanent imprint. You recall all the channel marker rules from the sailing courses you’ve taken, but without the imprint they don’t register in real time when you’re out there sailing; and thus the mistake is made, and then the imprint is scored into the cerebral penduncle, and now you’re actually learning real seamanship.

The beauty of sailing on the San Francisco Bay is that you learn soon enough how to deal with a grounding. I recalled the time I had the Fohn, a C&C 40, stuck in a mudbank directly in front of the Corinthian Yacht Club in Tiburon. Close enough for the salts at the bar to enjoy the spectacle through the huge picture window, with the cityfront of San Francisco providing a dramatic backdrop for the sailing vessel with all sails full yet apparently not moving. I dropped the jib and mainsail and ordered Brian, Marc, and Vic out onto the boom, and the Fohn heeled over 20 degrees giving the keel some room. Brian had the worst of it, straddling at the farthest outboard point, when I revved the engine to 3000 rpm and began criss-crossing my way out of the mudflats. He howled like a cowboy, or was it the shrill cry of a school girl? as the boom came gibing about in wild fashion while the Fohn broke free. I fell to the cockpit sole laughing and could not get up.

I knew I could never convince Pam, Lindsay, and Julian to hike out on the boom like Brian, Marc, and Vic. So I applied all the available torque the diesel could provide and began the same criss-crossing, rocking technique. It worked and the boat popped back into the channel while I released one hand from the wheel to pat myself on my own back. Another imprint was scored, and seamanship prevailed.

We eased into the Drake Channel and felt our first gust of the Christmas Winds. The boat heeled a few degrees, and then I recalled in horror that I had not properly flushed the head. The bowl was good and full when we pulled out of the dock, for I could not flush it in the harbor. I had made a mental note to flush it when we reached open water in the channel. Somewhere in the process that mental note got pushed down the stack. Another penduncle post-it note gone missing. I jumped down the companionway and into the head, and sure enough there it was, a great stinky mess dripping onto the sole. The towels drying on the rack had of course fallen down into it. I partially swooned cleaning it up.

From your sailing courses you learn to wear your gloves when handling a line, and to always make sure a line under load is secure. I released the jib furling line to let out the sail but failed to wrap the bitter end around a cleat. The Christmas Winds caught the sail and it came flying out as the furling line ran out wildly and cut a crease in my ungloved hands and burned the skin off three fingers.

I was scoring imprints now at a prodigious rate. “Calamity mistake number three,” I noted. Three calamities and we were yet to actually sail the boat.

We sailed across the channel to Cooper Island. We were handling the boat properly now and the sailing was good as the wind freshened up to 20 knots. The mooring field at Cooper Island was mostly full as the smart cruisers had grabbed a mooring before the afternoon rush. We found a couple moorings still available at the farthest points out and made a plan of attack. The NE trades were fairly howling now, and the northern point of Cooper Island was causing a wind sheer that increased the velocity to 25 or 30 knots. We approached the mooring but as we reached it and backed down to stop the boat’s way the wind blew the bow off in a direction away from the mooring. No problem, I told the crew, we’ll just try it again.

And so on for the second attempt. The bow was blown off, and there was not sufficient time for Lindsay to get hold of the mooring pennant before the boat began sailing away from the mooring ball at speed.

And so on for the third, fourth, and fifth attempts. Pam, Lindsay, and Julian were all offering passionate advice on how to steer the boat. Each time one of them would grab the pennant the boat would arc away, and with only a boat hook to pull the 20,000 pound sailboat back to the mooring ball the simple physics of the matter overcame all Herculean attempts at raw strength. On one of the attempts we managed to wrap a mooring line around the lifeline, nearly bending a stanchion with the weight of the boat before getting the line free. On another attempt we were able to hook the pennant and then secure the mooring line to a cleat, only to find the line wrapped around the keel and pulling the boat amidships up to the mooring. The crew nearly mutinied when I insisted that we release the line and try again. The verbal assaults were flying now from bow to cockpit and back, and even the 30-knot gusts could not silence the insults and oaths.

Now we had all agreed that on this trip to BVI we would learn how to take up a mooring without raising our voices, as we noticed that the most experienced cruisers were capable of. All this was tossed over the side. There was not a cruiser moored at Cooper Island that afternoon that did not hear the various curses, shouts, and wailings from the boat trying to secure itself at the farthermost mooring.

These were gusts I had not yet experienced — great screaming williwas of katabatic squamish wind in a profound Venturi. And they seemed to blow hardest each time we stopped the boat precisely at the mooring ball.

I finally abandoned that particular mooring, not from want of trying, but because on the sixth pass I managed to drive over it with the prop in forward, thus cutting off the pennant line altogether. I was doing really well — not. I had terrified my crew, disturbed the tranquility of the anchorage, and deprived another sailor from using the now useless mooring ball.

After a dozen attempts we were finally settled and secure. Down in the cozy salon we ate our supper and listened to the howling of the wind without a care.

‘Round midnight the calamities started up again. I was lying in my bunk and thinking about all the strain on the mooring line. I should have set two lines. The wind was still whistling shrilly in the rigging, deck hardware was rattling everywhere, and the boat was arcing around in a wild restless motion. I went up on deck and secured a second line from a bow cleat through the mooring pennant and to the other bow cleat. As I made may way back to the cockpit I noticed the inflatable dinghy. It was inverted. The prop shaft of the outboard motor stood straight up as the outboard head served as a keel. Thankfully I had taken care to secure the gas tank with a line.

It wasn’t easy to right the dinghy, for when we lifted it it wanted to fly away like a kite. But we managed to do so and the salt water ran in rivulets from the outboard engine housing. We went back to our warm bunk feeling the security of the second mooring line and a sense of accomplishment.

The next morning the williwaws were still gushing past Cooper Island as we slipped the mooring and ran south on the six-foot swells. Down-island we ran, licking our wounds, broad-reaching down to Norman Island. We were anxious to get into the calm waters of The Bight. The dinghy also seemed anxious to get there, and surfed down the waves on our stern in a vain attempt to overtake us. Day Two was proving to be a marvelous day of glorious downwind sailing.

We were tied to a mooring in protected waters a couple of hours later. I dived over the side and inspected the prop, and sure enough there was the tangled mass of mooring pennant that I had severed at Cooper Island. I sawed away at it with a knife and then deposited the heap on the swim platform, where it managed to remain undisturbed for the next eight days.

With a few hand tools from the ship’s stores I jumped into the dinghy and proceeded to take apart the outboard engine head. I inspected and cleaned and dried, but did not prime the carburetor with gasoline. I pulled on the rope again and again, but the ignition would not ignite, and the mute sputtering told me it was time to call The Moorings. Pam had been telling me this for an hour or so, but of course I needed to prove that I could get the water out of the engine myself, or prove it not.

A rastaman appeared an hour later in a whaler with a couple of serious outboards behind. He inspected my half-disassembled engine and repeated some of the steps I had done. He also primed it with fresh gas. I offered him a beer as he sweated in the afternoon sun, for it seemed to me that all men should drink beer religiously in BVI. He declined, for rastamen do not drink, and accepted a cold Perrier.

“Good water,” he announced with a grin after having a taste.

Away he pulled on the starter cord, once, twice, thrice, and so on for about a minute, and then stopped and rested. I was sure that it would not start, for after my unsuccessful attempts and the attempts of the rastaman, surely the engine would never start again.

He rested a moment and had a long pull from the Perrier.

“It will start this time,” he declared. And with one final pull the engine roared back to life. And a moment later he was back in the whaler and roaring out of the mooring field and back into the channel.

With the dinghy in service we were now able to leave the boat. Pam and the boys and I jumped in and headed straight to the Willie T for lunch, a Painkiller, and a jump from the poop deck of this floating steel-hulled barge. This floating restaurant and bar is named after William Thornton, an eighteenth century polymath who was born in Jost Van Dyke from British Quakers who built the first sugar plantations in BVI. He left the islands at age five to be educated in Lancashire, became an teenage apprentice to a physician and apothecary, then a writer and painter, then a doctor, visited the US with a letter of introduction to Benjamin Franklin, visited Paris, won a competition for designing the new US Capital in 1793 with a design influenced by the Louvre and the Pantheon, and later was appointed by Thomas Jefferson to oversee the new US Patent Office.

In the bar on the upper deck we found that the Obscene Santa was still there. We discovered him the year before, on Christmas Eve, a plastic Santa doll above the bar that sported a shamefully ignominious spar that danced up and down with the movement of Santa’s hips. William Thornton’s mother, who he never saw from age five until he returned to BVI at age 27, would have fainted.

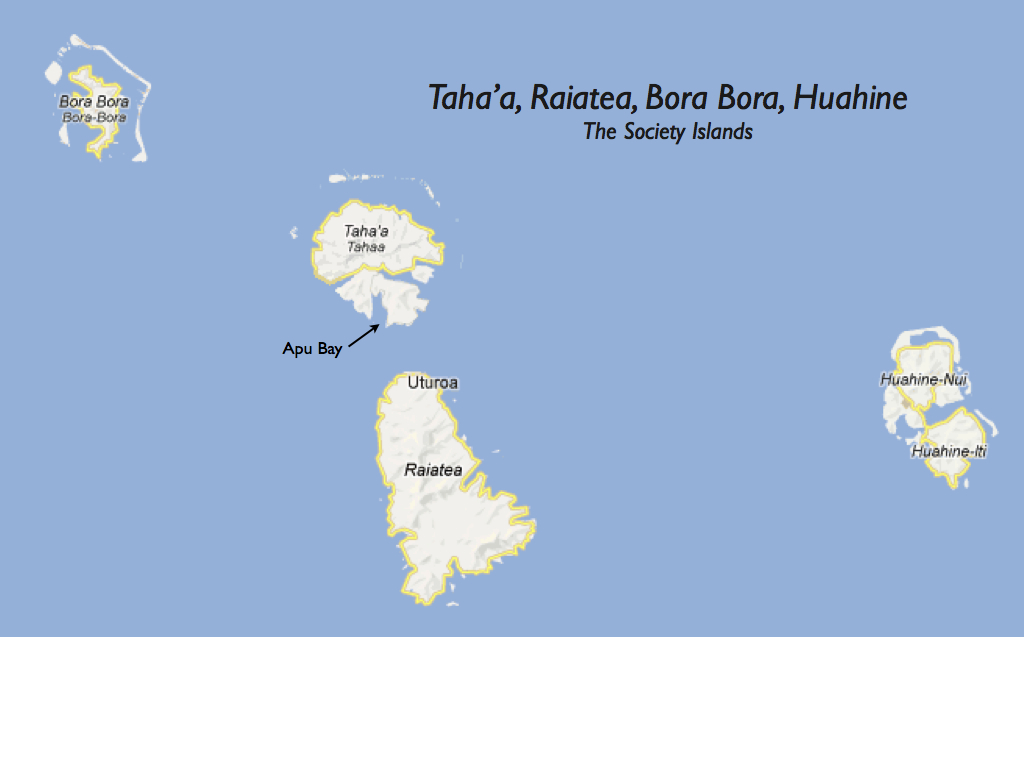

I was hell-bent on getting to Jost Van Dyke for New Year’s. Great Harbor, the small bight on the southern side of Jost Van Dyke, was home to Foxy’s, and every year hundreds of boats rafted up for a raucous New Year’s Eve celebration. In the months before leaving for BVI I had scoured every chart to determine how I could get to White Bay, a small anchorage just west of Great Harbor, in time to get a mooring before the sailing horde arrived. So early the next morning I slipped my lines and sailed past the Indians and through The Narrows to Jost Van Dyke. It was another morning of glorious sailing, as all mornings inevitably turn out to be in BVI.

We tied up in White Bay without any of the antics from Cooper Island. The crew were starting to get good at this. To actually tie to the mooring I had to wake up the boys. As teenagers, they are happiest when lying asleep in a bunk, at least until the sun had reached its noon zenith. We were starting to get into the groove of cruising, and shouting about a mooring seemed like a breach of equanimity. Something a lubber would do.

White Bay was white and pristine. On the shore our toes dug into the sandy floor of Ivan’s Stress-Free Bar. I imagined coming back to Ivan’s one day with my guitar and entertaining the sparse crowd with my folky originals and 60’s recreations with shades of blue, as I imagine in every tropical bar I enter. To sail a boat to a stress-free bar and play music until The End, this is a formula that explains existence. It organizes all philosophic thought from Pythagoras to James into a dialectic stew pot in which the theists, atheists, agnostics, epicureans, and fatalists congeal into consensus from the roux of wind, sun, and freedom.

Meanwhile, a half mile down the beach a cruise ship anchored and began dispatching a series of land-bound launches. In another hour there were a couple hundred people at the far end of the beach clogging up the Soggy Dollar Bar, another of Jost Van Dyke’s treasures, named by the currency offered by cruisers who swim to shore for an afternoon respite. From Ivan’s we walked down the beach and into the crowd, taking note of the sense of urgency of the well-dressed vacationers who chatted on cell phones on the beach. Feeling superior, for we had our own boat and thus ultimate control of destiny, we rode the dinghy back to our boat, then set off for Great Harbor and Foxy’s.

“This is an island dog,” proclaimed Foxy as he rocked on his restaurant veranda. He pointed to a sleeping black labrador at his feet.

“Oh?”

“Do you know why he’s an island dog?” Foxy questioned me.

“No sir … er … Mr. Foxy.”

“Because he’s black. He sits on his ass all day long. And he don’t know who his daddy is.” And with that he took another pull from his drink. It was four in the afternoon and he seemed serenely blitzed as he rocked away in his famous restaurant and bar tucked away in a corner of paradise. I felt I needed to catch up.

It was still a few days before New Years Eve. With all my planning I had managed to get to White Bay a full three days before New Year’s. I had to choose between the great New Year’s Eve party at Foxy’s and the raft-up of hundreds of boats, against the prospects of sailing on to the north. Once again we slipped our lines and set sail for more adventures.

For onward lie The Baths of Virgin Gorda, the expansive North Sound, Trellis Bay with its artists burning great caged effigies on New Year’s Eve, and not least — back to Norman Island for one last Painkiller on the Willie T with the Obscene Santa.